Attribution and Citation on Twitter

May 31, 2017

The post Attribution and Citation on Twitter appeared first on Plagiarism Today and is reprinted with permission.

BY JONATHON BAILEY: As a social network, Twitter was built to be fast and public. Twitter was meant to be used anywhere on any device (even by via text messaging in its early days). The services focuses on removing barriers to sharing data in a bid to give it an immediacy other social networks often lack.

But the streamlining of sharing, the character limit and the format of Twitter in general meant that some sacrifices had to be made. Long form content has never really been practical, images were often limited and, most importantly for this post, citation often took a backseat.

However, Twitter has made a lot of adjustments to its formula since it’s founding in 2006. Many of those shifts have targeted attribution and citation directly, finding ways to make it easier to share what others are say while leaving attribution intact.

So, to understand how to cite and attribute on Twitter, we first must take a look at how those standards developed over time and why they are the way they are today.

A Brief History of Citation on Twitter

![]()

When Twitter first launched, there was really no tool for attributing or citing tweets. If you wanted to repeat what someone else had said on Twitter, citing it was pretty much up to you and that could be difficult with the 140 character limit.

With no top-down standard, Twitter users began to develop their own.

At first Twitter users started to use the @username method of identifying other users. Catching onto this, Twitter began to automatically link @username references, first calling them Replies and then, in March 2009, calling them Mentions.

The move from Replies to Mentions was a significant one. Previously, Twitter users would only see if someone mentioned them with an@username if it was at the beginning of the tweet. That would convert the tweet to a semi-private message that only followers of both users would see.

This brought about an interesting convention among users known as the .@username or the “dot reply” where users would place a period before @username to ensure the message would be tweeted publicly without having the rearrange the tweet.

For example, if I wanted to say “@PatrickOkeefe is a great guy!” but make sure the world knew it, I would instead say “.@PatrickOkeefe is a great guy!” However, @PatrickOkeefe would not necessarily be alerted to this.

By converting replies to mentions, users saw all instances of their name being mentioned. This included dot replies but also mentions later in the tweet.

However, that still didn’t make it simple to repeat a tweet you liked. If you wanted to “Retweet” someone there was a different convention, known as the RT.

To do this you would put RT @username and then the body of the tweet. So, if you wanted to Retweet my example above, you would use “RT @plagiarismtoday .@PatrickOkeefe is a great guy!”

The problems with this were legion. The “RT @username” ate into the character count, often requiring the tweet to be edited. This gave rise to the “Modified Tweet” when that happened. That required users to use “MT @username” to indicate that it was changed.

In November 2009, Twitter pushed live its Retweet button. This replaced the “RT @username” style of retweet, now known as a “manual retweet”. Now, instead of manually inserting attribution, Twitter places the original tweet in the retweeter’s timeline with a note of why it’s there.

However, modified tweets did hang around for a while in cases where users wanted to add their comments. That too was done way with in April 2015 when Twitter added the “Retweet with Comment” feature.

Since then, Twitter’s focus has been on easing the 140 character limit. In September 2016 Twitter made it so that gifs, images, polls and quoted tweets no longer count against the limit. In March 2017, they did the same for replies (though not mentions in the tweet itself).

The story of Twitter is one user developing citation standards and Twitter following up later to implement them more effectively by baking them into the product itself.

With that history lesson out of the way, we can now look at how citation and attribution works on Twitter (as of today at least).

Sharing

When it comes to sharing content that you see on Twitter with your followers, Twitter is the home of the retweet.

The retweet function simply takes the tweet and shares it on your timeline as is. Using the retweet function keeps the same username and the same avatar as the original tweet, but it adds a note saying who it was that retweeted it.

The function also allows the person doing the retweeting to add a comment, a functionality similar to the modified tweet standard from the early years of Twitter.

Things, however, get more complicated when you attempt to retweet a retweet.

If you retweet a non-commented or non-modified retweet, you are simply retweeting the original tweet. The middle person, the one you are following who did the original retweet, receives no credit or attribution.

However, if you retweet one with a comment, the retweet goes to the comment on the tweet, which includes a link to the source. This continues as additional retweets take place, with each retweet containing a link to the tweet below it.

Bear in mind though that manual retweets are deeply frowned upon on Twitter today. Though many users were initially reluctant to accept the retweet function, now the function is pretty much standard with the old “RT” standard being seen as roundly inferior.

All in all though, the process of sharing content you find on Twitter with your Twitter followers is literally as easy as the click of a button. However, things do get more complicated when you are trying to bring outside content into Twitter.

Linking and Tagging

As with Facebook and most other social networks, the primary tool for citing outside content brought into the service is linking.

When you paste a link into Twitter, Twitter automatically shortens the URL (to reduce the impact on the character count) and convert it into a clickable link.

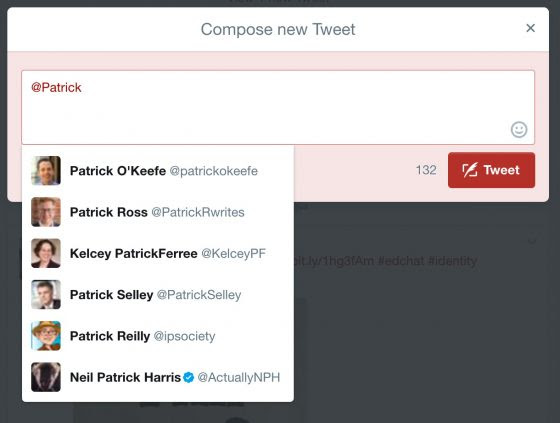

However, often times on Twitter you’ll want to also give credit to the Twitter user behind the work. That can be done following the above @username standard. Best of all, when composing a Tweet, simply typing the “@” and then starting to type the name will give you a dropdown where you can select them.

Doing this while linking to outside content is not necessarily a requirement though it is considered a positive thing to do, especially if there’s room in the character count. It’s also worth noting that, if you click on the “Tweet” button on a website, including this one, you’ll have the username autofilled through addendum that says “via @username”.

This practice is as much to notify the site that you’re tweeting their content as it is to provide additional attribution. However, if you can do it, it’s generally advisable because it’s a great way to interact with the people whose content you’re sharing.

All in all, despite the differences on the platform, the process of linking and tagging outside content is very similar on Twitter to how it works on Facebook: Fairly simple and straightforward.

Embedding and Linking to Tweets

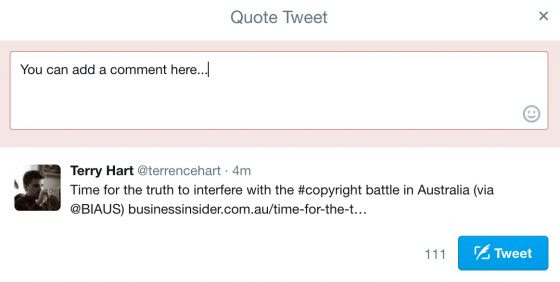

If you want to take a tweet you see on Twitter and reference on your site, there are two ways to do so: Linking and embedding.

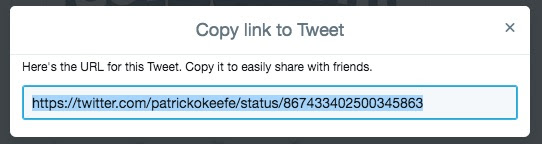

To do either all you have to do is click the downward arrow at the top right-hand corner of the tweet and then click either “Copy link to Tweet” or “Embed Tweet”.

(Note: As with the other items in this article, this focuses on using Twitter from the web interface. If you’re using an app, including the official Twitter app, the process may be different.)

If you click the copy link button, you will simply get a popup that gives you a URL to copy. That URL serves as a permalink directly to the original tweet. It’s that simple.

Embedding is slightly more complicated but not much more so.

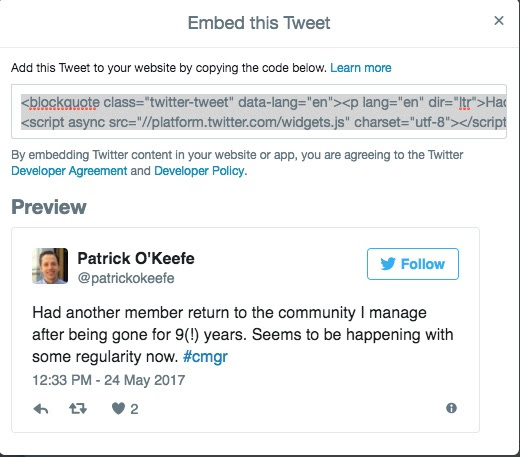

Clicking the “Embed Tweet” link gives you a similar popup but this one provides HTML code that you can copy and paste into your site along with a preview of the final product.

The embedded Tweet includes the avatar and name of the original author and a convenient “Follow” button that makes it easy for visitors to follow the person on Twitter.

However, if you use WordPress you can actually embed the tweet via the copy link function. Simply copy the URL and then paste it directly into the article, WordPress will actually convert it into an embedded tweet without having to look at any of the code.

Using the tweet above, here’s an example of what an embedded tweet looks like after you place it in your site.

Had another member return to the community I manage after being gone for 9(!) years. Seems to be happening with some regularity now. #cmgr

— Patrick O’Keefe (@patrickokeefe) May 24, 2017

All in all, the process is extremely simple and doesn’t require a great deal of technical expertise. There is little to no reason why anyone should struggle with citing content found first on Twitter.

A Note on Privacy

Twitter’s privacy settings are far more simple than Facebook’s. On Twitter, tweets are either public or they are protected, meaning they are available only to permitted followers.

If a user protects their tweets, you will not be able to use the retweet function on them. You can use manual retweets, but that is considered inappropriate both from a citation and a privacy standpoint. The code to embed tweet is similarly unavailable on protected tweets.

Tweets can also be deleted after the fact. If that tweet had been retweeted, the retweets will cease to exist though if it’s retweeted with comment the comment will be available and a “Tweet Unavailable” will replace the original tweet.

However, if you embed a tweet that’s later deleted, the text of the tweet will remain though any media in the tweet will not show up. This prevents deleted tweets from breaking external websites.

The main thing though is that, if you can’t retweet or embed a tweet using the Twitter-provided tools, don’t do so. The user has clearly indicated they don’t want their tweets seen outside of their followers and making them public is frowned upon.

Twitter doesn’t have much in the way of privacy controls, but it’s important to respect the ones they do have.

Bottom Line

All in all, Twitter’s history is one of watching their community create citation standards and then implementing them directly.

Every step of the way there was pushback from users who were adverse to the changes. Yet, every time, those changes were eventually adopted and the previous way of doing things was abandoned.

This has created something of a cycle. Twitter users change how Twitter operates, then those changes, in turn, impact how the service is used. One study found that the retweet and mention changes have greatly increased the number of retweets and reduced public replies.

Twitter is in a constant state of evolution and much of that progress has targeted citation. That’s why I fear this article may become out of date quickly, as Twitter concocts new tools to streamline sharing and attribution.

Still, it’s interesting how the service has evolved and how the users have changed with it.

Categorized in: Blog, copyright infringement, Copyright Law, Culture, social media